Political trends in the Arab World and their impact on investments

Presentation by Yaqut President Peter Cross to the third annual Arab Mining & Minerals conference and exhibition, London, November 7, 2018

Around a quarter century ago, when I had not long started out in the business of political risk consultancy, I had an interesting conversation with one of our clients, who asked me which country I thought had the highest political risk factor. Before I could finish humming and hahing, he gave his view, which was: “The United States”.

I was rather taken aback — especially given that at the time we were advising his company on a very sizeable potential investment in Algeria — which had just witnessed, in quick succession, the end of the one-party regime, multi-party elections that the Islamic Salvation Front had been poised to win, a barely disguised military coup, the assassination of President Boudiaf by a member of his own security detail, and the beginning of a savage islamist insurgency.

He explained his view thus: the United States had so many different jurisdictions — county, city, state, federal — and so many elections, that laws and regulations could change at any time, as could the officials one has to deal with. And then everything can be challenged in court, again at numerous levels. And frequently is. In other words, for our client, political risk boiled down to unpredictability. And doing business in the United States had a particularly high incidence of political risk because it was a functioning (albeit sui generis) democracy. The point is that political risk can mean rather different things to different people.

Let us look instead at the parameters of political risk as laid down by the insurance industry. These comprise, broadly:

- Political violence (war, revolution, insurrection, civil unrest)

- Expropriation or confiscation of assets by the host government

- Repudiation or obstruction of contracts by the host government

- Unexpected and disruptive changes of legislation, regulations or other ground rules that are assumed to be more or less lasting

- Inconvertibility of foreign currency and/or bars on the repatriation of profits

- Sovereign debt default

In short: things that happen to states, and things that are done by states, that may adversely impact a company’s business. In contrast to our former client’s take, the insurance industry’s view of political risk focusses on events that might be expected to have very serious consequences for business operations, but which in “normal” times generally have a low level of incidence.

But there is also the key question of time-scale. Different business sectors will attach differing degrees of importance to short-term or long-term factors of risk. Hedge funds, for instance, may need to be more attentive to relatively short-term politico-economic trends that could result in, say, President Erdogan formally ending central bank independence or the Saudi authorities putting an end to the riyal-dollar peg. The extractive industries, on the other hand, with very substantial investments pinned down typically for decades, have an entirely different perspective. They will need a far closer understanding of longer-term factors potentially affecting regime stability, inter-state conflict, the permanence or otherwise of fundamental assumptions in terms of investment policy, and so on (while of course also, once an investment decision has been taken, keeping a close day-to-day eye on relations with decision-makers and other key stakeholders — including local communities — and on a host of other factors of risk that are sometimes defined otherwise: security risk, operational risk, compliance risk, reputational risk and so on).

Lenin once observed: “There are decades where nothing happens, and there are weeks where decades happen”. And I don’t think one needs to be a card-carrying Leninist to agree that we are living through just such a period in which events appear to have been greatly accelerated. I would suggest that what we are witnessing is the simultaneous maturing of any number of long-term, and even very long-term processes, some of them largely unnoticed until recently, but which are suddenly bearing fruit — creating visible events — in the here and now.

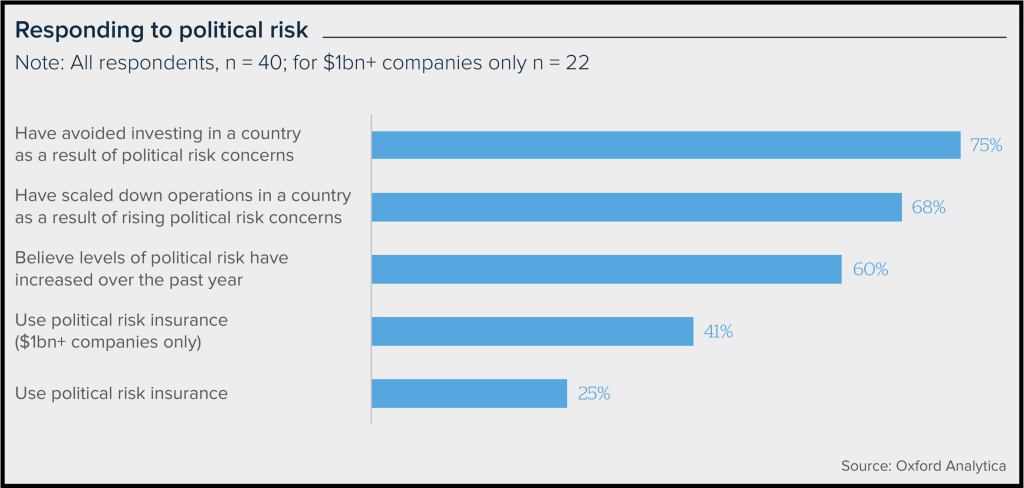

This widespread perception that we are living in a more eventful, less predictable, riskier world also comes through in business surveys.

Insurers Willis Towers Watson and Oxford Analytica put out a very interesting report in September, based on a survey of around 40 of the world’s leading firms:

- 60% of respondents reported that political risk levels had increased since last year.

- Nearly 70% stated that they had scaled back operations in a country as a result of political risk concerns or losses, and slightly more than that reported holding back from planned investment due to political risk concerns.

- More than a third of companies surveyed said they had actually suffered political risk losses in recent years — rising to over half of companies with annual revenues in excess of $1bn, with one mining sector respondent reporting that losses relating to political risk had averaged $700m per year over the past three years.

As for the types of political risk events that had incurred losses exchange transfer losses led the field, with political violence in second place (followed by import or export embargos, expropriation and, finally, sovereign default).

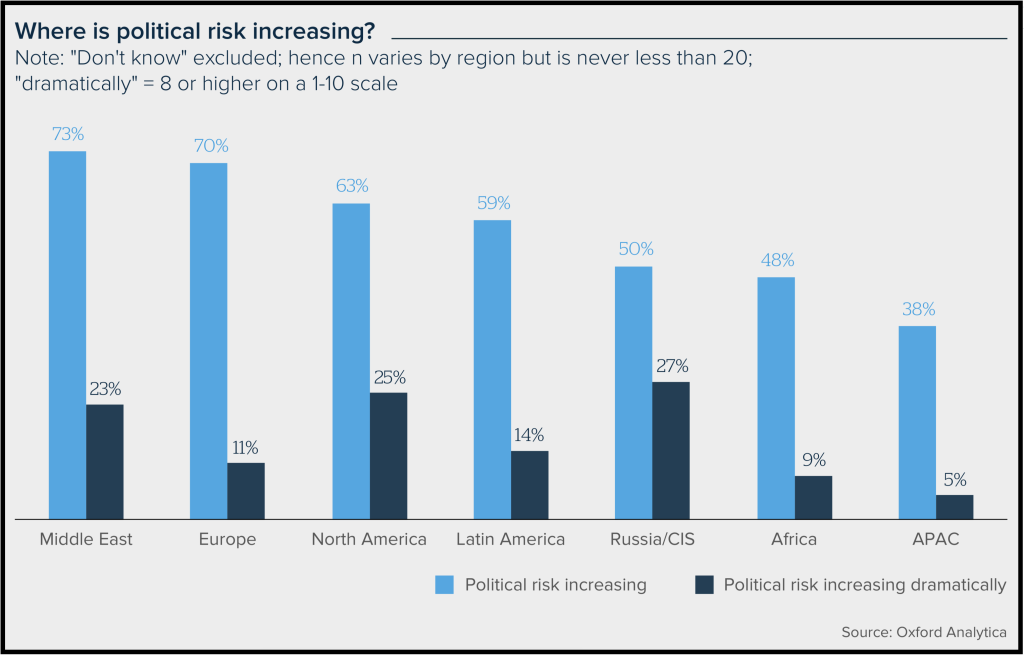

The Middle East was the region most often cited — by almost three quarters of respondents — when asked where they felt political risk was increasing.

In the Middle East, some of these long-term processes and trends nowadays appear obvious, having been brought dramatically to light by the Arab Spring — a series of tumultuous events that hardly anyone predicted, in part because very few had their eye on those underlying, slow-maturing trends.

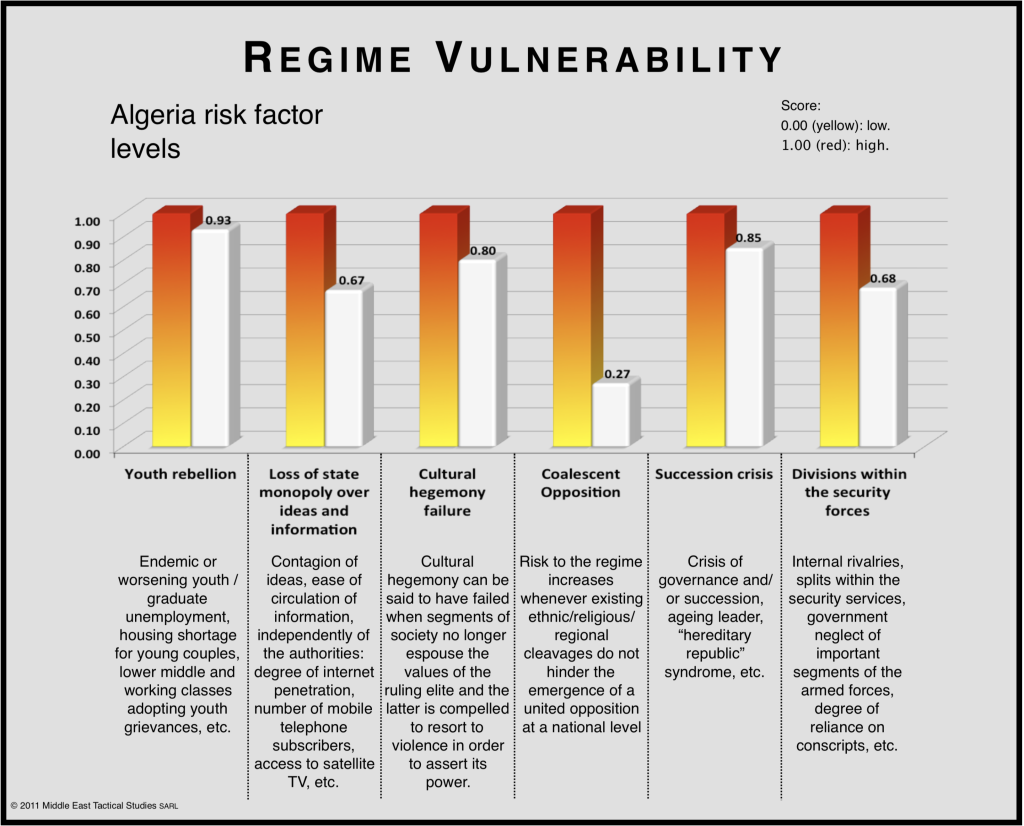

To recap briefly some of the trends we identified at the time as fuelling the Arab uprisings of 2011 (this chart, which dates from April 2012, was produced by Middle East Tactical Studies, Yaqut’s ancestor; these were rough and ready tools that we put together at the time to try to evaluate month on month how the processes were playing out in several countries we were working on).

We grouped those trends under six broad headings:

- Youth rebellion (or rather the mainly socio-economic factors driving the revolt of Arab youth, notably chronic unemployment and housing shortages).

- Loss of state monopoly over the dissemination of information & ideas (in particular with the rise first of satellite TV, then internet, then social media and the generalisation of smart-phone ownership).

- The breakdown of cultural hegemony (or the degree to which the broad mass of the population continues to adhere to the ideology and values espoused by the elite — Arab nationalism, or specific local nationalisms, or the triad of ‘God, King & Country’ in say Morocco (traditionally) or Saudi Arabia (more recently).

- Coalescent opposition (the degree to which forces opposed to the regime in place are able to transcend often deep-rooted differences — religious, ethnic, regional …)

- A succession crisis (one manifestation of this was the idea of tawrith, or of the ageing presidents of the nominal Arab republics, passing on the presidency to their sons — Hosni Mubarak to Gamal Mubarak, Ali Abdullah Saleh to his son Ahmad, etc. — which had become hugely controversial prior to 2011, fuelling divisions among the ruling elite).

- Divisions within the security forces (including the key question of whether or not rank and file troops and police could be relied upon to follow orders).

It is very much worth bearing in mind that, to varying degrees across the countries of the region, many of these factors remain present and unresolved.

Even as far as the ‘coalescent opposition’ rubric is concerned — the factor that might seem to be the least relevant after the vicious bloodletting that followed the failure of the Arab Spring revolts — there is a serious argument to be made that Sunni-Shiite sectarianism — which is frequently depicted as a constant but is in fact anything but — may have peaked and begun to recede. This would certainly appear to be the case in Iraq, for example.

But if the more or less long-term processes that produced 2011 are now out in the open, might there perhaps be other trends that are still submerged, or neglected? And if so, what sorts of risks might they portend for investors, and the mining industry in particular?

We would like to suggest a handful of factors — by no means an exhaustive or definitive list — that we believe are worth keeping an eye on in the coming period.

Firstly, the US shale revolution.

- Since around 2005, US domestic oil and gas production have been rising dramatically, thanks largely to the development of shale production. In 2011, the United States became a net exporter of refined petroleum products, and in terms of total energy consumption, the US is now around 90% self-sufficient. The corollary is declining US reliance on Middle Eastern oil.

- And one very important consequence of this is likely to be the erosion of the so-called the Quincy Pact — the arrangement dating back to the meeting between King Abdulaziz, the founder of the present day kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and President Roosevelt on board the USS Quincy in February 1945 whereby the US has guaranteed Saudi Arabia’s military security in exchange for secure access to supplies of oil.

- If it is no longer in the United States’ vital interest to continue providing that essential security guarantee to Saudi Arabia and the other Arab Gulf states — and there were clearly fears that this was coming to be the case in the Obama years — then there are clear implications for the security, and indeed internal stability, of those states.

Secondly, Turkey’s eastern pivot.

- Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s foreign policy has gone through several phases since the AKP came to power in 2002, but until fairly recently one constant had been Turkey’s EU accession bid. There now seem to be few illusions on either side that this will ever come to fruition (although keeping the process alive, just about, is a useful fiction for both Ankara and Brussels, given that Turkey’s provisional customs union with the EU depends on this).

- If and when breaking point is reached, this can only reinforce Erdogan’s easterly shift in focus, which is already quite visible, with increasingly open and grandiose ambitions for leadership of the Muslim world.

- What this already seems to be contributing to is the crystallisation of not two power blocs — broadly Saudi and Iranian — but three, with Turkey already reeling in Qatar and doubtless ready to pounce on any new opportunities.

- This process, combined with the declining US interest in the region, has fuelled a new development: the power-houses of the new blocs are establishing permanent extra-territorial bases in other countries of the region.

- This plainly increases the possibility of inter-state conflict, and even more so of a three-way regional cold war (of which we can already see the beginnings) — played out more through proxy conflicts, destabilisation manoeuvres and other dirty tricks than through direct military confrontation.

- As we have seen in the case of the Saudi-Emirati led embargo of Qatar, there may be efforts to drag foreign investors into such confrontations, summoning them to choose sides between the rival camps.

Third, increasingly intense Russian involvement in the region.

- Since Vladimir Putin’s third presidential term, the Russian Federation has adopted a noticeably more assertive foreign policy worldwide, and part of this has been an increasingly concerted effort to recapture lost ground in the Middle East. This has moved from building close cooperation with Iran, in nuclear energy notably, to actively promoting both weapons sales and cross-investments with numerous countries in the region, and, most obviously, the very deep involvement of the Russian military in the Syrian civil war — which appears to have saved the Baath regime.

- Even before the direct Russian military intervention in Syria as of September 2017, the influence of Russia on the conduct of the war was clear — Damascus had effectively emulated the Russian Federation’s Chechnya playbook.

- This leads one to wonder whether, if Russian diplomatic and economic penetration of the region continues over the coming years, further examples of affinity and emulation might be seen in countries that establish privileged ties with Moscow in the economic sphere as well. Given the numerous expropriation incidents that have affected foreign investors in Russia’s natural resources sector in recent years, this is a potential development that miners with an interest in the region may find worth tracking.

Fourth, climate change.

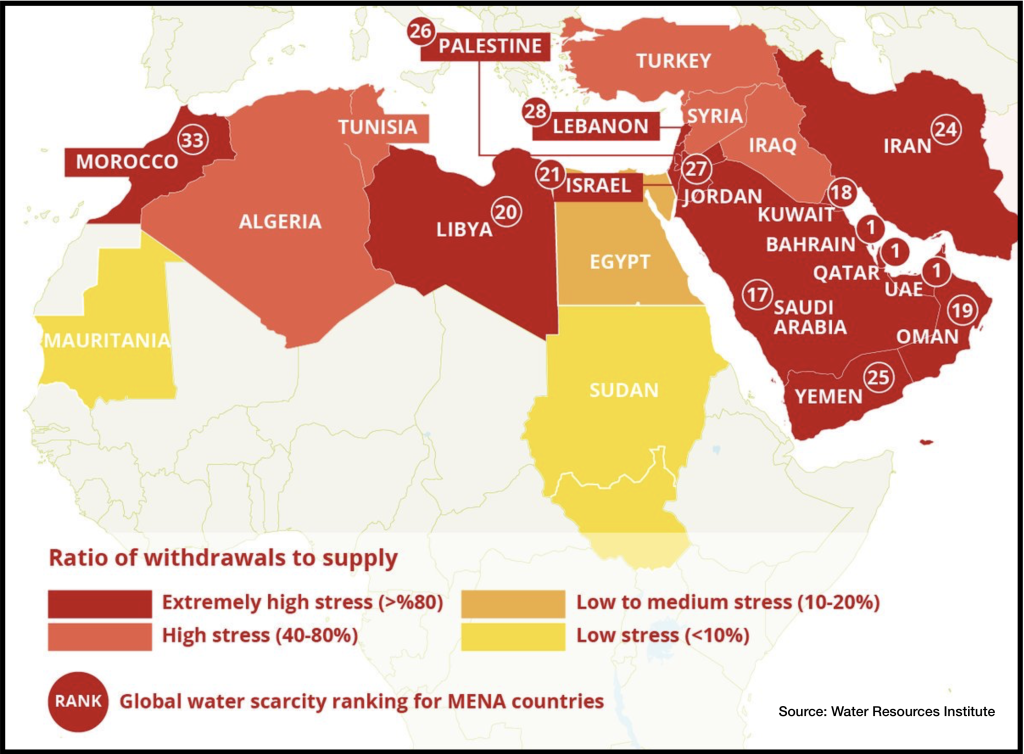

- All the countries of the region are subject to one degree or another to water stress. Climate change is already exacerbating this situation: droughts are becoming longer and more frequent, making non-irrigated farming on marginal land increasingly hazardous.

- This has already had noticeable effects. It has been argued that the Syrian revolution was in part fuelled by the migration of large numbers of farming families to the large cities such as Hama, Aleppo and Damascus under the impact of severe drought in the years prior to 2011. Although this is clearly only part of the story, it is worth noting that a similar process of rural-urban displacement as a result of recurrent drought is currently under way in parts of neighbouring Iraq.

- Competition for increasingly precious water resources between states — along the Tigris and Euphrates and in the Nile basin — already exists can be expected to intensify.

- But it is also worth considering the possibility — even the likelihood — of competition within states over water use. And in particular between everyday household consumption, which is growing as populations grow, and industry — notably the mining industry. And while some miners operating in water stressed environments around the world have made significant progress in water saving, care will have to be exercised in making choices — if use of water for dust reduction is cut, for example, this may foster other problems in terms of public health (Barrick Gold I believe ran into serious difficulties with the local population in Mahd Al-Dhahab, Saudi Arabia, because of widespread local health problems attributed to dust from their mining operation).

Finally, the possibility of a resource nationalism, which goes hand in hand with high commodity prices.

- Here, I would like to look back for a moment, to the example of Algeria in the 2000s. After President Bouteflika came to power in 1999, his Minister of Energy and Mining Chakib Khelil proceeded to draw up a free-market oriented reform of the oil and gas sector that would, amongst other things, allow 100% ownership by foreign oil companies of E&P blocks. At that time, oil prices were languishing at below $25/barrel. By the time Khelil’s legislation was passed by the Algerian parliament in the spring of 2005, however, prices had begun a very long rally — and the new Hydrocarbons Law was never gazetted, President Bouteflika having had something of an economic nationalist epiphany along the way. Subsequently a series of amendments were imposed by Presidential order that essentially gutted Khelil’s law, restoring Sonatrach’s compulsory 51% majority stake in upstream ventures and imposing a special surcharge on IOCs windfall profits when prices were above $30/barrel (amendments that were approved unanimously by the same Algerian parliament in October 2006).

- By mid-2008 — while oil prices peaked at around $150/barrel – Bouteflika’s nationalist bravado had extended to the rest of the economy, with the introduction of the now famous 49-51 rule, imposing minimum 51% Algerian participation in projects involving foreign investors, restricting the repatriation of profits, etc.

- At the time we noted a degree of emulation of the Kremlin’s version of resource nationalism, which we argued went hand in hand with clear affinities between Bouteflika’s style of rule and Putin’s.

In conclusion:

Monitoring, analysing & above all taking account of political risk are essential but complex tasks — that unfortunately do not always fit particularly well with established processes of Enterprise Risk Management or ERM.

They may also have rather different finalities, depending on whether we are addressing a pre- or post-investment decision situation.

Once an investment decision has been made, the point obviously is to mitigate risk to the project over its life-cycle.

In advance of the investment decision, on the other hand, the finality may be simply risk avoidance — in other words, to determine whether a negative decision is warranted.

But it may also serve to elaborate risk management strategies for projects that might be subject to rising political risk but where returns may also be correspondingly high — conferring a competitive advantage for companies that are ready to go down that route on the basis of properly informed choices.